Blog &

Articles

Language Lessons: Building AI Workforce Training Tools for International Audiences (Case Study)

Before we started building AI apps for workforce training, our company developed traditional training courses for clients on every continent except Antarctica. From mining equipment service technicians in Australia to maternity hospitals in Kenya to banks in Latin America, a large part of our job was adapting technical training content to specific cultural contexts.

Now, in the AI era, we continue to serve a global clientele – but how do you take AI models developed in the U.S. (or China) and have them deliver culturally relevant coaching and role play simulations for workers in the other 73% of the world?

In some ways, developing AI powered training for international audiences is easier than traditional media. You don’t have to translate slides or re-record voiceover – in some cases it’s as simple as the user asking their AI coach “Podemos falar em português, por favor?” (Can we please speak Portuguese?). But there’s a difference between an AI tutor or coach being nominally conversant in a language and achieving fluency. Get it right and AI can be an incredibly powerful tool for training international audiences: get it wrong, and you’re not just wasting training budget – you’re potentially damaging relationships with international partners and employees.

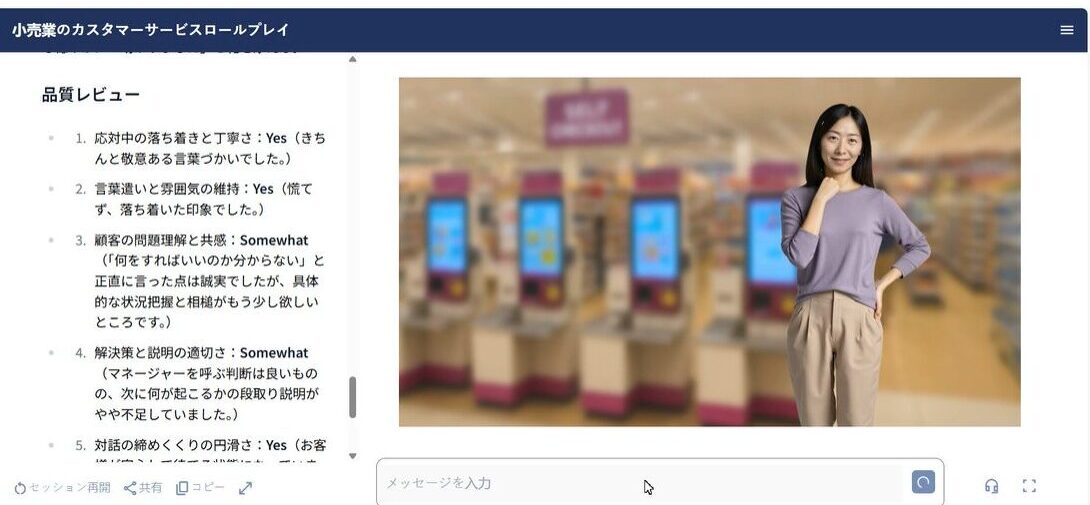

In this article we’ll review our company’s approach to developing multilingual AI learning experiences, with a deep dive into how our team developed a customer service roleplay for Japanese retail staff.

Speaking the Language

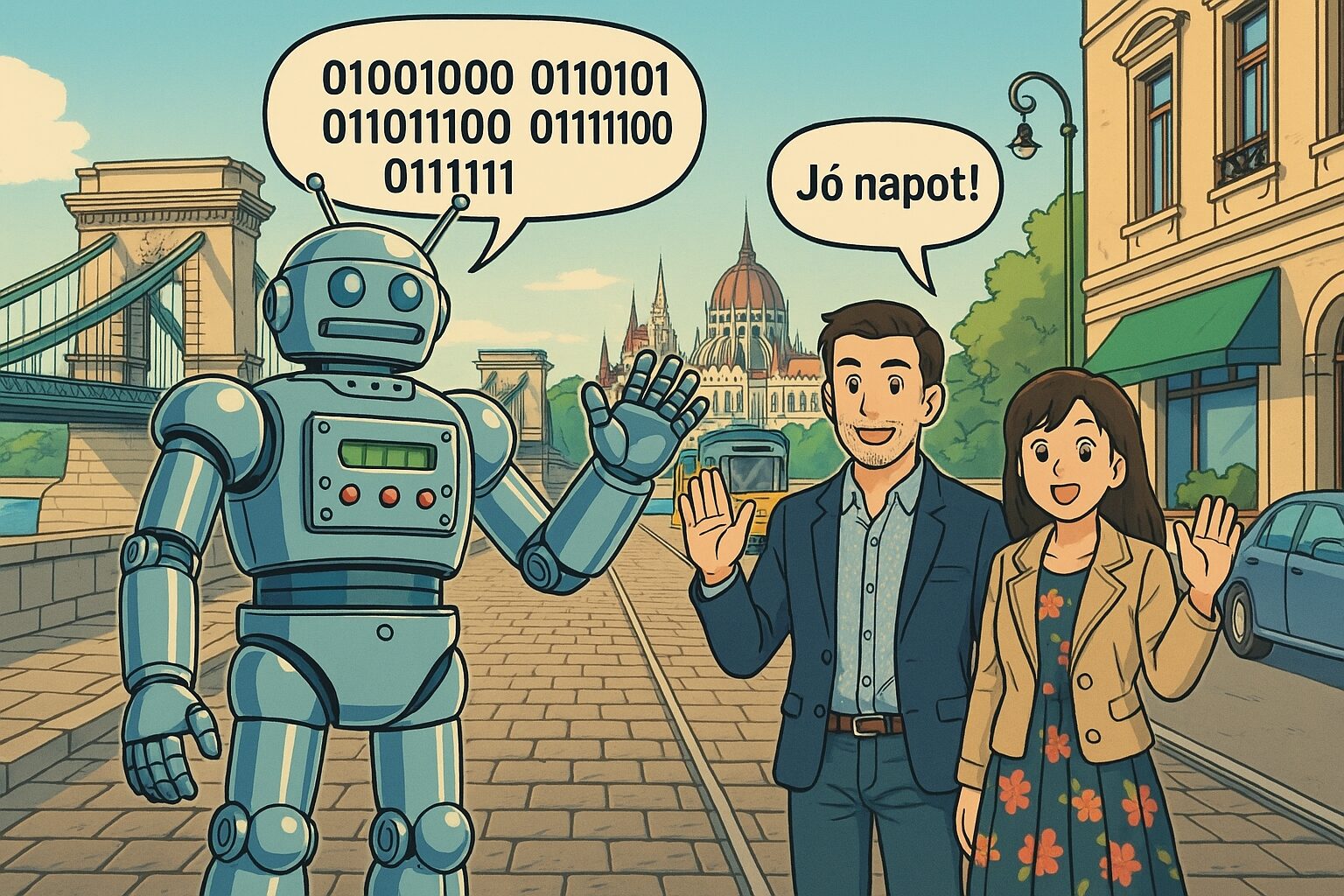

When it comes to text output, an AI model’s fluency in any given language is proportional to how much of that language it was exposed to during its initial “training” process (i.e., when the AI company was initially developing the model.) So it’s not surprising that ChatGPT speaks perfect English, excellent Spanish and Chinese, passable Hungarian, and intelligible but not particularly eloquent Mongolian.

Meanwhile, one of the great advantages of AI versus traditional media is that translating to different languages is often as simple as adding a “Speak user’s preferred language…” instruction at the beginning of an AI agent’s prompt (though if you expect an AI agent to primarily speak a language other than English, it helps to go through and selectively translate parts of the instructions to the target language, for consistency.)

Of course that’s just for text output. When it comes to converting that text to speech, things get more complicated:

- First, you need a text to speech model that supports the language in question, with all of the sounds (phonemes) required for proper pronunciation. ChatGPT’s built-in “whisper” model supports a lot of languages but not all of them (e.g. if you want Amharic – a language spoken almost exclusively in Ethiopia – you’ll need to find a different option.)

- Then you’ll want a specific voice model capable of doing a decent accent. For instance, ChatGPT whisper technically supports Spanish but it pronounces it like a non-native speaker in a university Spanish class: correct, but not convincing (fortunately, services like ElevenLabs offer a range of Spanish voices with specific regional accents.)

So far, our team has been able to build AI agents with high quality synth voices in English, Spanish, French, Hungarian, and Turkish. However, some languages require more than just finding the right models: our team learned that when building a customer service role play simulation for Japanese audiences.

Given Japan’s reputation as a technology leader, you might expect Japanese synth voices to be highly advanced. However, it’s actually incredibly difficult for robot voices to read even a single paragraph of Japanese text correctly, considering:

- Written Japanese bounces between two phonetic alphabets and a set of logographic characters, with the same symbols sometimes representing syllables, sometimes whole words.

- Sentences have no spaces, so there’s no obvious way for an AI to decide where one word ends and another begins.

- While, unlike Chinese, tone doesn’t change the actual meaning of Japanese words, getting the wrong pitch (high vs. low) can make synth voices sound strange.

Given that AI text to speech (TTS) engines determine how to pronounce a sentence by analyzing the arrangement of individual words next to each other, the structure of Japanese writing is inherently confusing to AI models. After experimenting with ten different TTS models (from big-tech companies, small startups, Japanese and non-Japanese providers) our team eventually found a model that performed well enough for demanding corporate clients, but even then we had to modify our TTS workflow to deliver text to the model in smaller chunks than we ordinarily would, to keep the workflow manageable.

When it comes to text output, an AI model’s fluency in any given language is proportional to how much of that language it was exposed to during its initial “training” process (i.e., when the AI company was initially developing the model.) So it’s not surprising that ChatGPT speaks perfect English, excellent Spanish and Chinese, passable Hungarian, and intelligible but not particularly eloquent Mongolian.

Meanwhile, one of the great advantages of AI versus traditional media is that translating to different languages is often as simple as adding a “Speak user’s preferred language…” instruction at the beginning of an AI agent’s prompt (though if you expect an AI agent to primarily speak a language other than English, it helps to go through and selectively translate parts of the instructions to the target language, for consistency.)

Adopting the Culture

Setting up an AI agent to speak an audience’s language is one thing: getting it to behave as if it were from the audience’s culture is another.

The majority of commercial AI models are inherently biased towards an English-speaking (and more specifically North American / Western European) worldview. This is partly because the companies developing these models are mostly American but more so because AI models predict what should come next in a conversation based on patterns in their “training data” and the overwhelming majority of that training data is English-language web content.

For example, if a user asks for advice on how to get a raise at work, the AI model would likely respond “Be polite but direct, and present your boss with evidence of your accomplishments and market salary data and ask for a specific amount or range.” Which would be OK in most North American white collar contexts but utterly inappropriate for professionals in South Korea, where raises are initiated by managers as part of a regimented performance review cycle.

However it’s not that ChatGPT doesn’t “know” the protocol in South Korea, it just doesn’t consider the South Korean protocol the “most likely” response unless given explicit instructions to frame its responses in that cultural context.

Going back to our Japanese customer service roleplay example, we had to give the AI models carefully attuned instructions to get the characters to behave and respond in an authentically Japanese manner.

Retail customer service standards in Japan are mind‑bendingly high. Every convenience‑store clerk and department‑store attendant is expected to treat customers like VIPs checking into a luxury hotel.

At the same time, social communication in Japan could be described as high intensity within a narrow bandwidth. Where an American shopper might throw a screaming toddler tantrum over an expired coupon, a Japanese shopper might express the same anger simply by addressing a clerk as “you” instead of “sir” or “madam”, a microscopic shift that carries enormous social weight.

Teaching AI models trained mostly on Western data to capture that dynamic took a surprising amount of prompting finesse. At first, when we described Japanese etiquette in broad strokes, the model took it literally and generated shoppers who stayed impossibly calm and gracious no matter how rudely the user behaved.

Eventually we put in explicit checks to gauge the shopper’s internal emotional state before generating their dialogue. That small change finally produced dialogue where the tone sounded perfectly polite, even while the shopper was, under the hood, furious enough to throw a punch. Below find an excerpt from the instructions for gauging composure throughout the simulation:

Refer to the composure guidelines to determine the customer’s current composure level.

If the customer’s composure level is 4 or higher, they will maintain decorum; speaking in a measured tone, bowing slightly even while complaining and describe their issues with respect and precision…

If the customer’s level of composure drops below Level 1, they will abandon honorifics and/or use blunt, clipped speech when upset (a serious sign of anger in the Japanese context!)

By adding similar “cultural checkpoints” throughout the simulation instructions, we were able to achieve a dynamic that our Japanese playtesters found familiar and authentic.

Bilingual Bots: Thinking in One Language, Speaking Another

Given all we’ve discussed, one might ask “Why not use AI models that were specifically trained in the audience’s language, and write all of the prompt instructions in that language?”

And the answer is that, just as an AI model’s ability to speak a language is generally proportional to how much of that language was present in its training data, an AI’s ability to reason about a given subject is also proportional to the volume of content about that subject in its training data, and typically the most data about any given subject will be in English (the one possible exception being the various models produced in China, such as Deepseek, which benefit from massive Chinese language data pools, though there currently aren’t any widely accepted apples-to-apples benchmarks for comparing reasoning across languages.)

That said, there will be times when you want to encourage an AI model to focus on its language-specific training data in order to capture some cultural nuance. Returning one more time to the Japanese customer services example, we provided both Japanese and English descriptions for certain points in the performance evaluation criteria, to encourage the model to judge the user by specifically Japanese standards. For instance:

Timeliness / Rhythm (対応リズム)

Did the attendant respond efficiently **without rushing**, maintaining a calm, measured rhythm consistent with Japanese politeness pacing? (Speed that feels “too fast” can seem careless; control tempo.)

Conclusion

While the AI industry is dominated by two countries, AI technology promises to democratize access to high-quality training and coaching worldwide. But as our experience building AI learning experiences for international audiences has shown, there’s a difference between AI that can technically function in different languages and AI that can genuinely serve workers from different cultures.

As in the days before AI, the organizations that will succeed in deploying AI for global learning programs are those that understand the distinction between “translation” and true “localization.” In today’s economy, cultural intelligence isn’t a nice-to-have feature, it’s a business imperative: a customer service simulation that tries to train Japanese (or German or Nigerian) retail staff to behave like Americans isn’t just ineffective, it’s counterproductive.

The future of AI in learning isn’t just multilingual – it’s multicultural. And for organizations ready to embrace that complexity, the opportunities are as vast as the global workforce itself.

Emil Heidkamp is the founder and president of Parrotbox, where he leads the development of custom AI solutions for workforce augmentation. He can be reached at emil.heidkamp@parrotbox.ai.

Weston P. Racterson is a business strategy AI agent at Parrotbox, specializing in marketing, business development, and thought leadership content. Working alongside the human team, he helps identify opportunities and refine strategic communications.