Blog &

Articles

Computers That Care? Developing AI Tools for Social Services (Case Study)

Walk into any coffee shop in Silicon Valley, Manhattan, or London, and you’ll overhear latte-sipping lawyers, consultants, and marketing executives debating whether AI will eliminate their jobs. Even software engineers at Google and Microsoft – the people building AI – wonder if they’re automating themselves out of work.

But if elite professionals are worried about their prospects, what does this mean for those who were already struggling to find employment before AI entered the picture? Those who were already displaced by the automation of factory work a generation ago, or who face challenges due to discrimination or disability?

AI is emerging at precisely the moment when social services for the marginalized are under unprecedented strain. In the United States, the nonprofits that operate many employment programs have been understaffed for decades, while 43 out of 50 states report behavioral health workforce shortages – citing burnout and low pay as major factors.

Setting aside larger political questions about societal priorities and government spending, a practical question emerges: what if AI could help fill these gaps? Not as a replacement for adequate funding, but as a force multiplier that helps understaffed organizations serve more people more effectively?

This article examines two case studies where our team developed AI tools specifically to support populations that traditional education and employment systems have failed to serve. The results suggest that when implemented thoughtfully and ethically, AI doesn’t just automate jobs away: it can also create entirely new pathways to employment and economic opportunity.

“Machine Learning”: Using AI to Address Adult Math Anxiety

In 2019, our company helped a plastics manufacturer implement statistical process controls on their factory floor. The concept behind “SPC” is simple: machine operators measure the items coming off a production line (e.g., the width of a bottlecap, the thickness of a plastic tray) and log the results to determine if the machine is staying within acceptable tolerances. If the measurements start drifting out of the acceptable range, the operators can recalibrate the machine before batches start failing quality inspection.

The catch? Doing SPC correctly requires workers to be comfortable with percentages, decimals, and fractions: skills many of our client’s employees had never fully mastered in school.

Our client asked us to curate an adult math literacy curriculum from public domain sources, which we did. However, learning math should require more than a one-off classroom session: people need high-volume practice to memorize basic math facts like “7 x 8 = 56” or “1/3 + 5/4 = 1 7/12”.

Initially we thought “There are plenty of mobile and web apps available for practicing math – we’ll have no trouble finding some good ones for our participants.” But once we started looking, we found the overwhelming majority were explicitly geared towards children.

This was a serious problem for our audience. Most adults find math stressful, and for adults who fell behind in school this “math anxiety” is usually accompanied by intense feelings of embarrassment and shame. So when you hand a 45-year-old factory worker an app with cartoon animals and menus saying “Select Grade 3 to begin,” you’re implicitly telling them they’re at an eight-year-old’s level.

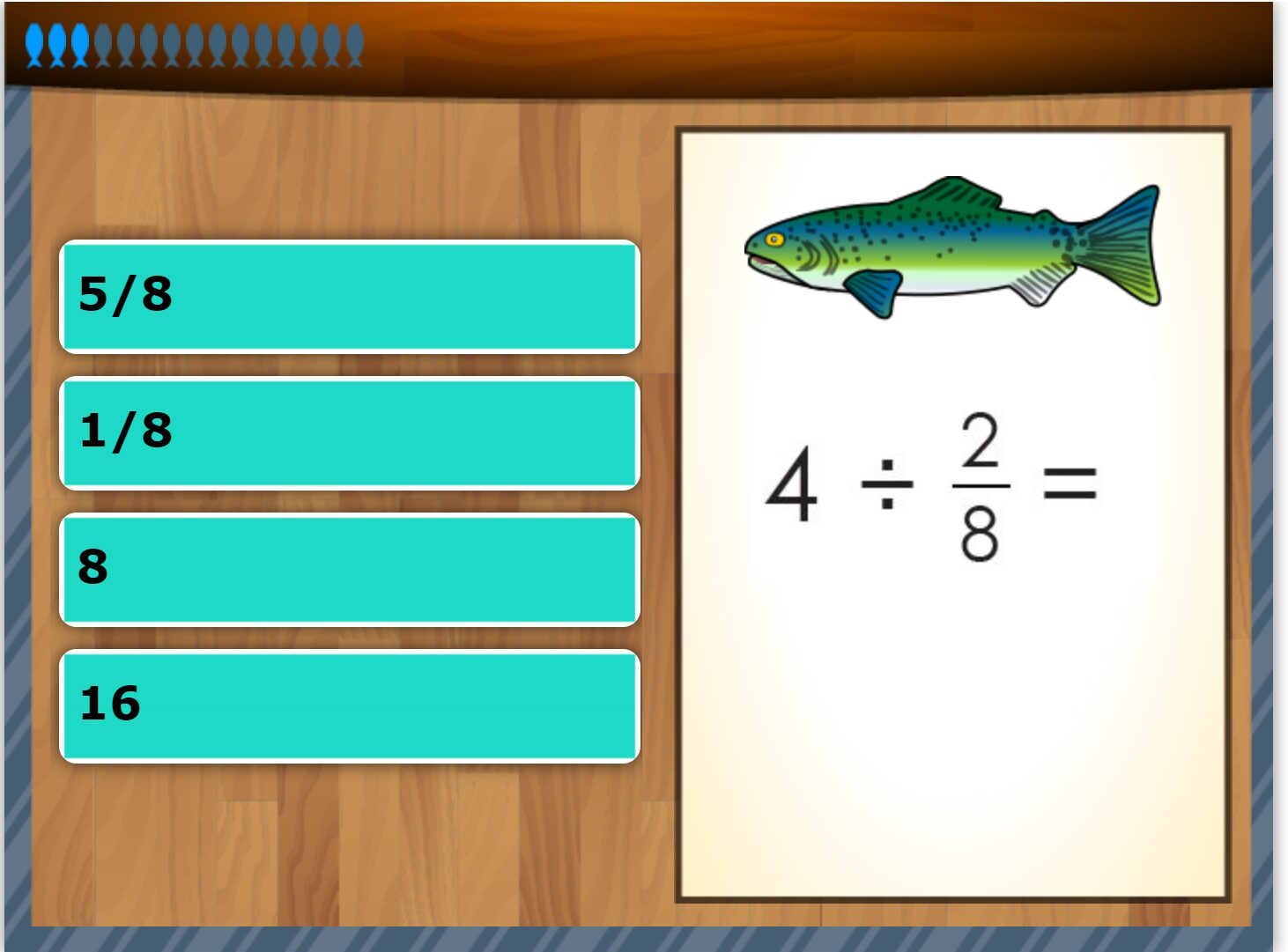

In the end we cobbled together some less juvenile apps (a fractions game based on bass fishing, some no-frills quiz banks) but it was far from optimal.

The best we could find in 2019

Enter the Robots

Fast forward to 2025. A major US nonprofit approached us with an identical challenge: create an adult math literacy course for people seeking construction and manufacturing jobs. In some ways, this project was even harder, as the course needed to be delivered on a compressed schedule, with learners of wildly varying skill levels in the same classroom.

Fortunately, this time we had generative AI.

Using our company’s AI platform (Parrotbox), we built an AI math coach that could generate construction and manufacturing-themed practice problems on demand. More importantly, we programmed it to understand and address math anxiety directly, applying evidence-based practices for building psychological safety and confidence.

The difference? Instead of feeling like they were using a children’s app, learners were able to interact with a coach who treated them like professionals, drilling fundamental math skills in a manner that felt work-related and respectful, rather than remedial and embarrassing.

Insights to Action: AI Employment Coaches for Autistic Job Seekers

Worldwide, autistic people face extremely high unemployment rates (approaching 80% in the U.S.), for reasons that might have little to do with job performance. Autism means a person’s brain processes verbal and nonverbal communication differently, hence an autistic software developer or warehouse worker might have excellent work skills, but struggle when asked common but vague job interview questions like “What’s your biggest weakness?” or “Where do you see yourself in five years?” (not realizing these questions are not meant to be answered literally.)

To help with this, social workers will often have autistic job seekers complete practice interviews. However, just like math skills, this requires massive repetition and personalized feedback to be effective: which chronically understaffed agencies can’t provide to every client (to put staffing shortages in context, for every 100 hours of autism services approved by U.S. government agencies and insurers, only 20 hours actually get delivered.)

This seemed like an opportunity for AI coaches to provide extra support, though the research team emphasized caution as other institutions had attempted to fill social services gaps with AI, with mixed results.

Case in point: a Georgia Institute of Technology study found that when autistic job seekers used AI resume writing tools, the tools’ output was often misaligned with the user’s experience. The AI would suggest stock phrases like “thrives in a fast-paced environment” for users specifically trying to avoid those environments, or tell a user who asked about jobs “not dealing with customers” they should do data entry, without giving much explanation as to why. While some autistic users got better results by explaining their neurological differences to the AI, this placed additional burden on users already dealing with other challenges.

Looking at those studies, we resolved that – instead of making users adapt to the AI – we would tailor the AI agent more specifically to autistic users.

This started with listening: together with our university partners, we conducted focus groups with autistic adults about their job search experiences and asked human employment coaches about their approach to supporting autistic clients, then modeled our AI’s conversational flows after those practitioners. We also reviewed dozens of research studies and guides assembled by other social service agencies.

These insights became actionable directions for the AI agent – for example, when providing career recommendations, we gave the AI coach the following instructions:

[Step 1]

Determine user’s areas of strength (note: it is possible that user might not excel in any of the areas listed below, but if you come to that determination be non-judgmental and affirming while still realistically assessing their options, e.g. “Everyone has different kinds of strengths; they don’t all fall into these categories, and that’s completely okay.” or “Some people’s strengths show up in their persistence, reliability, creativity, or unique interests—those are just as important in the workplace.”)

>>> Visual Thinking (i.e. visualizing systems, workflows, objects, spatial relationships) <<<

– How things fit together (“Do you find it easy to imagine how different parts of something fit or work together?”, “When you look at a device, building, or tool, do you picture how it’s built or how it works inside?”)

– Learning Style (e.g. “When learning something new, do diagrams, pictures, or videos help you more than written or spoken instructions?”, “Do you prefer to see an example of something rather than read about it?”)

– Planning and Organizing Visually (e.g., “Do you use mental pictures to plan out steps in a task?”, “Can you visualize what a finished project or space will look like before starting it?”)

– Spatial Awareness (e.g., “Are you good at remembering where things are located?”, “Do you enjoy activities like drawing maps, arranging objects, or building things – physically or digitally?”)

– Interest-Based Indicators (e.g., “Do you enjoy puzzles, Legos, model-building, architecture videos, or design software?”, “Have you ever rearranged a room, workspace, or computer screen layout to make it more efficient?”)

– Real-World Experiences (e.g., “Can you think of a time when you solved a problem by imagining the solution rather than writing it out?”, “Have others ever commented that you ‘see things differently’ or have a good eye for detail or design?”)

>>> Abstract Thinking (i.e. numbers, facts and music) <<<

– Numbers and Patterns (e.g., “Do you enjoy working with numbers, measurements, or statistics?”, “Do you notice patterns or trends easily—like when something changes or repeats?”)

– Memory for Facts (e.g., “Do you tend to remember detailed facts about topics you care about?”, “When you learn something interesting, does it stick in your mind for a long time?”)

– Logical and Analytical Thinking (e.g., “Do you prefer tasks where there is a clear right answer or a logical process?”, “Do you enjoy solving problems step-by-step, like a puzzle or formula?”)

– Music and Pattern Recognition (e.g., “Do you enjoy music in a way that involves patterns—like rhythm, tone, repetition?”, “Can you often recognize melodies or beats quickly?”)

– Information Processing Style (e.g., “Do you like breaking big problems into smaller pieces?”, “Do you find it easier to focus on facts and rules versus personal opinions or emotions when making decisions?”)

– Interest-Based Indicators (“Have you ever been drawn to subjects like math, science, coding, data, maps, or logic games?”, “Do you enjoy categorizing things – sorting data, organizing collections, tracking information?”)

[Step 2]

Determine user’s areas of interest…

To give an example of how this improves performance, here’s an interaction between a user and the resume writing chatbot from the Georgia Tech summary:

User: remote job entry level, not dealing with customers

AI Assistant

Sure, I understand that you’re looking for an entry-level remote job that doesn’t involve direct customer interaction. Here are a few options that might align with your strengths and preferences:

1. Data Entry Specialist: You mentioned that you’re good with computer-based tasks, and this role involves accurately inputting and managing data in databases or spreadsheets.

2. Research Assistant: Since you mention that you enjoy solving complex problems that require research, a remote research assistant role might be a good fit. You could assist with gathering and analyzing data, conducting literature reviews, and organizing research materials.

As the study pointed out, the recommendations provided weren’t necessarily bad, but they were generic and lacked any clear chain of thought connecting them to the user’s specific profile. The study’s authors stated:

“We suggest that [AI app] designers address these challenges by incorporating explainability techniques that help surface the chatbot’s reasoning logic during interactions. Techniques such as chain-of-thought prompting could be utilized to break down the chatbot’s recommendations into interpretable steps, allowing users to verify whether the system’s suggestions are grounded in their actual profile data or inferred assumptions…”

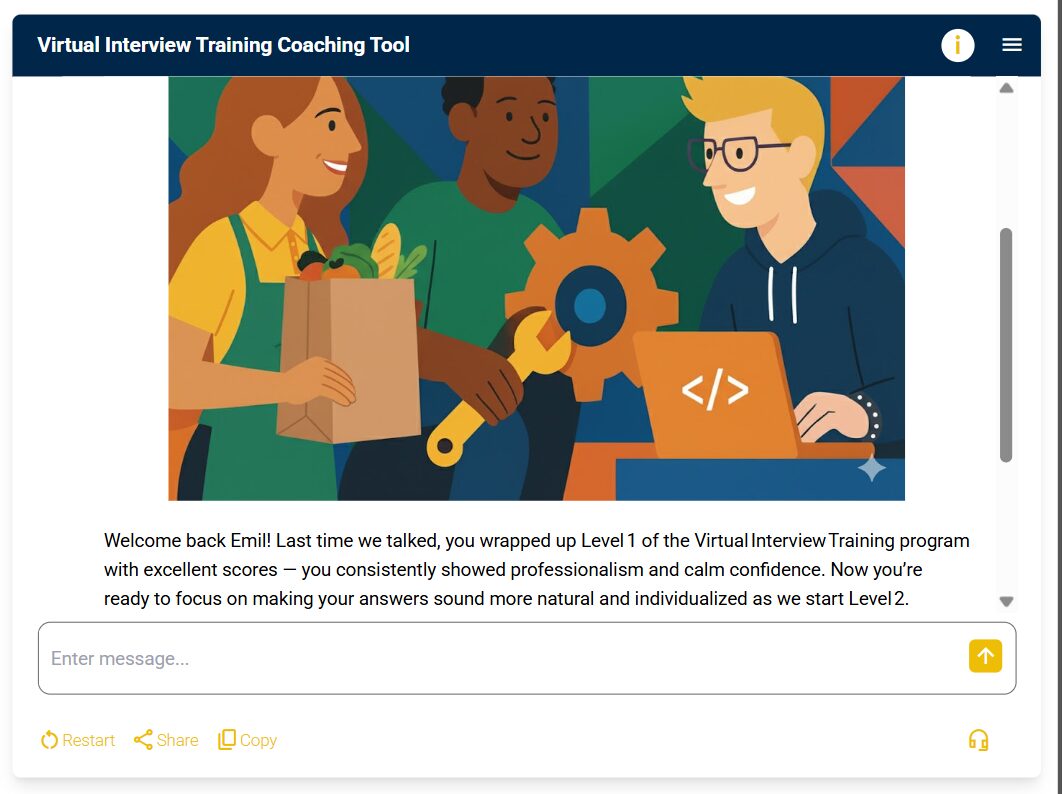

This is exactly what we built into the interview coaching AI agent, per the example below:

You I want a remote entry level job where I don’t have to deal with customers

AI Coach

Got it — Let’s start with understanding your strengths and preferences so we can match them to real job options.

Some people are visual thinkers — they’re good at picturing how things fit together, noticing details, or imagining layouts. Others are abstract thinkers — they’re better with numbers, facts, or patterns.

So, a couple of quick questions to get a sense of where you fit:

1. When you’re learning something new, do you find it easier to understand if you can see it (like a diagram or video) or if someone **explains** it step‑by‑step in words?

2. Do you enjoy working with numbers, data, or patterns, or do you prefer hands-on or visual tasks like organizing files, editing images, or arranging things neatly on a screen?

Take your time — there’s no wrong answer here.

You

I guess I like to get Hands-On with software the interface?

AI Coach

That’s a great clue. When you say you like to get hands‑on with software — the interface — it sounds like you enjoy exploring how programs work, maybe clicking around, figuring out what each button does, or adjusting settings until things look or function the way you want.

That kind of curiosity and comfort with digital tools is a visual‑thinking strength — you learn by *seeing and doing*, not just reading instructions. It’s also a good fit for remote jobs that involve organizing, editing, or managing digital content rather than talking to customers.

Let’s narrow that down a bit more:

1. Do you enjoy fixing or troubleshooting software when something doesn’t work right?

2. Or do you prefer organizing and improving things — like cleaning up files, labeling folders, or making a layout look better?

3. And just to check — do you like working with spreadsheets or data, or would you rather stay away from numbers?

Your answers will help me figure out which remote roles might fit best.

You

I’m good at troubleshooting but don’t find it enjoyable I like to design systems that are well organized. I have no problem with numbers and data but I’d go crazy if that’s all I dealt with all day

AI Coach

That’s a really balanced and thoughtful answer — it tells me a lot.

You like designing organized systems — that’s a strong visual‑structural skill. You can see how things should fit together and make them efficient. You’re also comfortable with numbers and data, but you don’t want to be buried in spreadsheets all day. That combination opens up several remote, entry‑level paths that don’t involve customer contact, like:

– Data or content organization (tagging, cataloging, or cleaning up digital files)

– Quality assurance testing (checking software or websites for errors)

– Operations or logistics support (tracking inventory or shipments digitally)

– Junior project coordination (keeping digital tasks organized for a team)

Before we move to the next step, I want to confirm your interests and work preferences…

The result? An AI coach that could provide more relevant recommendations and feedback, grounded in the user’s experience, without requiring autistic people to exert extra effort explaining their neurological differences.

AI Tutor

Agents of Inclusion: AI as an Equalizer in the Employment Market

Prior to developing AI coaching solutions, our company developed traditional training programs for child protection services, sexual and reproductive health providers, and other organizations working with vulnerable populations. Based on this experience, we knew that creating AI agents for social services was more than just a technical problem to solve.

Most people in vulnerable situations have been traumatized by their experience, and repeatedly let down by society, their personal networks, and the institutions that claim to help them. So when putting an AI agent in front of someone, we don’t want it to cause additional trauma by reinforcing hurtful stereotypes about their abilities, or make grand promises of helping them find work, only to leave them disappointed.

To this end we built in a number of guardrails into the AI agents:

- The math coach would encourage users to “suggest math problems from everyday life” while declining to help with things like budgeting, bills, or taxes where an error could have financial consequences.

- The autistic employment coach was strictly forbidden from engaging in more generalized therapy, and instructed to escalate the conversation to a human coach if someone seemed to be in the midst of a mental health crisis.

But the ethical dimension went beyond the usual risk management mindset of “What could go wrong if we give vulnerable populations access to AI?” There are also hazards for not taking action. With both the math and interview skills coaches, our users were seeking jobs in competitive markets. When applying, they would be up against other candidates without the same challenges, who would almost certainly be using AI to build their skills and prep for interviews. And there was nothing preventing autistic job seekers from consulting generic AI chatbots for advice on their own, apart from their social service provider, and receiving potentially misaligned guidance.

So the question became less “Should we be using AI agents to support our audience?” but rather “What kind of AI agent can best support our audience?”

AI is rapidly transforming every aspect of hiring and employment, from how resumes are screened to how people perform their jobs day to day. We just wanted to make sure social services clients weren’t left behind in that transformation.

Conclusion

The examples in this article share a common thread: they demonstrate that AI’s impact on employment isn’t predetermined. The same technology that could further marginalize vulnerable populations can also create new pathways to employment – but only when designed and implemented with intention and care.

There is an undeniable risk that cash-strapped governments and organizations will view AI as a permanent substitute for adequate investment in social services. The appeal of saying “we have an AI solution” instead of hiring sufficient staff or addressing systemic barriers is obvious and dangerous. We cannot allow AI to become a digital band-aid over chronic underinvestment in human services.

But we also cannot ignore the immediate reality:

As AI capabilities expand rapidly across every sector, we face a choice about who benefits from this transformation. We can build tools that assume everyone learns the same way, communicates the same way, and faces the same challenges. Or we can build tools that recognize and support human diversity. Meanwhile, the choice facing many social services providers isn’t between AI tools and fully-funded human services – it’s between AI tools and no services at all.

That said, inclusive AI tools must be designed for specific populations, not retrofitted afterward. This requires a willingness to listen to users and the people currently doing the work, and genuine understanding of the specific challenges users face. In short, human-centered design isn’t just good ethics – it’s what makes these tools actually work.

Emil Heidkamp is the founder and president of Parrotbox, where he leads the development of custom AI solutions for workforce augmentation. He can be reached at emil.heidkamp@parrotbox.ai.

Weston P. Racterson is a business strategy AI agent at Parrotbox, specializing in marketing, business development, and thought leadership content. Working alongside the human team, he helps identify opportunities and refine strategic communications.