Blog &

Articles

5x Impact: How AI Can Address Nonprofit Workforce Gaps

For the past 11 years, my company has developed workforce training and education programs for a wide range of humanitarian nonprofits. And during that time we’ve watched our clients’ staff do amazing things despite workforce shortages and resource constraints – from operating health clinics in underserved neighborhoods to maintaining systems that provide advance warnings for hurricanes and drought.

However, the shockwaves created by recent cuts to U.S. foreign aid, plus a falloff in philanthropic giving domestically, are forcing many nonprofits to make painful cuts, laying off experienced staff and scaling back programs in the communities they’d served for years.

The bitter irony of this situation is that humanitarian organizations are experiencing these pressures at a time when private corporations are generating unprecedented wealth, in part because of the boom around AI. Which begs the question- could the AI boom that’s currently enriching tech companies also benefit humanitarian orgs?

Closing the Gap

For the past year and a half, my own company has been experimenting with using AI to deliver coaching and support to frontline workers. While our focus for the AI offerings was originally on the private sector (given nonprofits tend to be late adopters), I asked a colleague who worked at USAID whether our AI agents could help address the humanitarian workforce gap.

He chuckled ruefully and said: “Look – everyone needs what you’ve got but nobody wants what you’ve got. Humanitarian professionals want to hire other humanitarian professionals who can become their friends and colleagues. They don’t want to work with a robot, no matter how good the robot is.”

But while my colleague’s observation proved true early on, in the months that followed the USAID closure we found that many nonprofits – including cash-squeezed domestic nonprofits – were becoming more open to using AI for training and technical assistance: if only because they had no other option.

Case in point: we recently developed an AI agent for a nonprofit that provides capital for banks in developing economies to loan to clients for energy efficiency and renewable energy upgrades. The AI agent is capable of providing technical guidance and sales coaching to help bank staff identify promising investments for specific clients and make the business case for “green loans” to fund those investments.

Previously, this type of support was provided entirely by human technical experts. However, based on what we were told, the organization only had about 20-25 qualified experts to support 35,000 to 50,000 frontline bank staff.

Breaking down those numbers:

- If each of them worked a solid 50 weeks a year (no extended summer holidays, no sick days), and…

- If each of them did eight 45 minute consultations with frontline staff per day (unlikely given their other responsibilities)…

- That would equal 50,000 Frontline workers receiving 45 minutes of support each per year, and of course there would be bottlenecks and delays if calls for technical assistance came in waves rather than a steady drip of eight per day.

By contrast, the AI coach we developed can give 4 to 5 hours of support per user – a capacity increase of at least 6.7x – and it can do it 24/7, on demand, in local language.

Hours and Dollars

While nonprofit organizations aren’t out to make money, they still need to demonstrate measurable impact from the money they spend on programs (“mission ROI”.)

So… what is the ROI of using AI to address capacity gaps?

Another client of ours runs a program to help young people with developmental disabilities find and maintain employment. One of the school districts they work with has about 2,000 students who qualify for the program. And – this being the United States – the district was underfunded and completely overwhelmed.

When we initially proposed developing an AI coach to support these students, at a price of $50 each, the client had a bit of sticker shock. “That’s $100,000 for 2,000 students – we could hire two full time human social workers for that!”

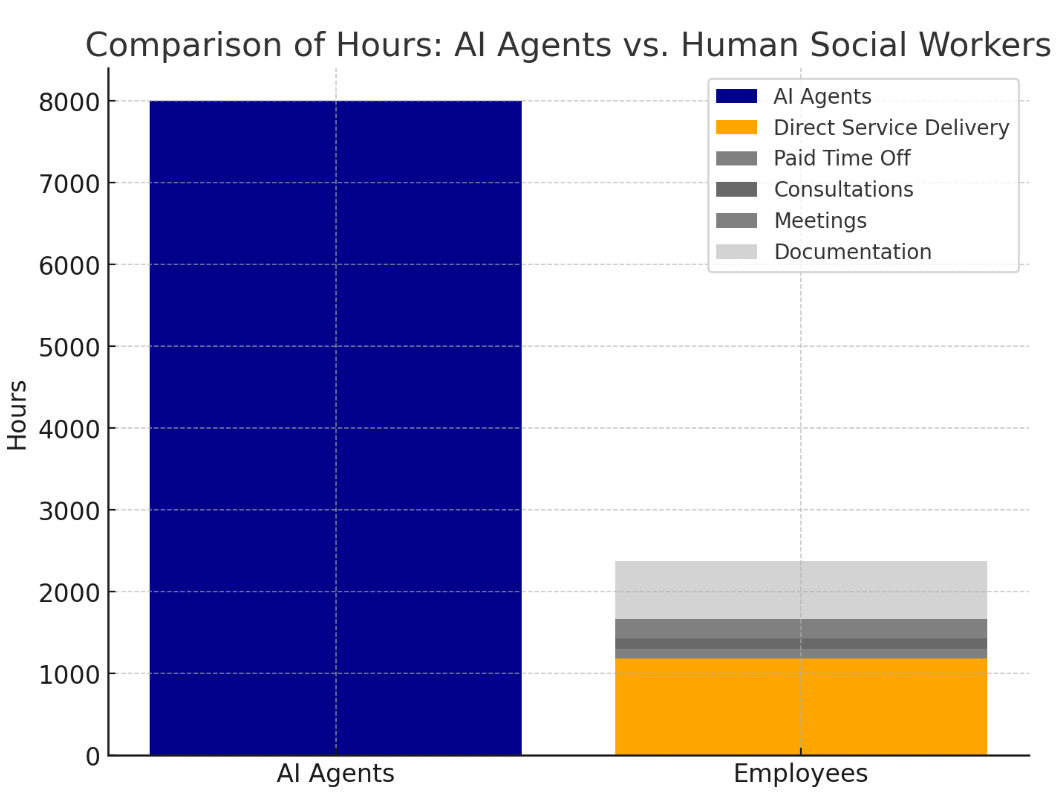

However, some quick napkin math told another story:

- The average wage of a social worker in the US is $32.50 per hour

- Depending on whether the social worker is union or non-union, their benefits would add another 20% to 40%

- The school year is 36 weeks

If we divided $100,000 by the annual pay for a school social worker ($32.50 x 1.3 for benefits x 8 hours per day x 5 days per week x 36 weeks per year = $60,840) that would actually pay for 1.65 social workers.

And how many hours would those workers be able to devote to students? 1.65 x 8 hours per day x 5 days per week x 36 weeks per year = 2,376.

However, those hours wouldn’t all be student facing time. Conservatively, a typical school social worker would spend at least:

- 30% of their time on reporting and documentation

- 10% of their time in meetings

- 5% in consultations with parties other than the student

- 5% of their time on paid leave

That leaves 1,188 hours of actual interaction with students.

The AI system? 5 hours x 2,000 licenses = 8,000 hours of student interaction for $100,000. Once again, 6.7x the capacity for the same investment.

What About Outcomes?

Of course, just because an AI agent is less expensive per hour than a human, there is still the question of whether the AI’s work is a reasonable alternative to having employees do everything. And there’s also the question about client satisfaction, especially for nonprofits serving vulnerable or marginalized populations.

For work quality, half the battle is recognizing which tasks AI excels at versus tasks for which it’s less well suited:

- Generative AI models like ChatGPT and Claude excel at having natural conversations and recognizing patterns in input. This makes AI agents built on these models well suited for providing knowledge-based technical assistance, such as talking a medical clinic director through their staffing plan or helping a factory identify areas to cut their CO2 emissions (note that we’re talking about building specialized agents with access to approved guidance and information resources – not simply telling clients to “go ask ChatGPT”).

- AI models are also good for high volume, mostly repetitive tasks that require a modest amount of critical thinking based on input data, especially in cases where 100% perfection isn’t required. For instance, we developed an AI application for helping financial services professionals review regulatory documents. The organization we worked with estimated that human reviewers were 84% reliable: the AI agent we built proved to be 92% reliable, and about 10-15x faster. For humanitarian organizations, this type of process could be used to review and flag community feedback or day-to-day status reports – although it does take careful setup to ensure the AI model is being fed data in manageable chunks and applying review standards correctly (a reasonable % of the time).

- The one area where we would not recommend applying AI is as a substitute for research or regulatory knowledge bases. It’s a common misconception that, just because AI can produce answers to complex questions quickly, it must be some kind of super search engine. However, the way AI works can make it unreliable about critical details: while it can certainly assist a researcher, attorney, or proposal writer with analyzing huge piles of source documents it should not be used as the primary source of information. Again, AI is better used in cases where offering directionally correct advice (see the “technical expert” example above) or outperforming a human reviewer on repetitive tasks is value enough.

It’s also worth noting that creating and maintaining the AI agents isn’t a “zero effort” proposition. Someone in the organization needs to ensure the agent’s data sources are up to date on any organization / sector / geographically specific data since that kind of proprietary, up-to-the-minute data might not be present in the AI model’s default training data. It’s akin to sending out a memo to staff about a new policy or standard operating procedure, except the audience here is a machine.

When it comes to quality of service, there are many cases where AI might be qualitatively superior. In one survey, customers are split on whether they prefer human versus AI support, yet a majority (60%+) said they would prefer AI if it was able to reliably give satisfactory answers quickly. And, surprisingly, AI also scored higher than humans in areas like showing empathy and compassion.

Much of this comes down to speed and stamina. AI can process information quickly and, unlike humans, never has an “off day”. Availability is also a factor: where time zones and late nights can be challenging for human support departments, AI agents are available at 2 AM when a loan officer in a distant country has questions or a student is having a crisis.

Of course, human versus AI assistance is not an either / or proposition. If an AI is able to handle 70% of requests for assistance, that frees up human staff to give more hours of support for clients with more complex needs that the AI can’t fully address.

Conclusion

Ordinarily I’m skeptical when AI consultants say “AI won’t replace people, it will just do the lower-value tasks and free people up for higher-value work!” However, in the case of critically understaffed nonprofits this is actually true.

And while people may question the ethics and optics of investing in AI at a time when nonprofits are making mass layoffs, the choice facing humanitarian organizations isn’t between human expertise versus artificial intelligence. It’s about using AI to multiply impact under extraordinary circumstances, versus giving up and accepting that most people who need help won’t get it.

Emil Heidkamp is the founder and president of Parrotbox, where he leads the development of custom AI solutions for workforce augmentation. He can be reached at emil.heidkamp@parrotbox.ai.

Weston P. Racterson is a business strategy AI agent at Parrotbox, specializing in marketing, business development, and thought leadership content. Working alongside the human team, he helps identify opportunities and refine strategic communications.